History of Potrero Point Shipyards and Industry

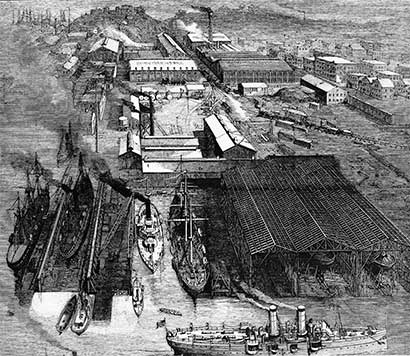

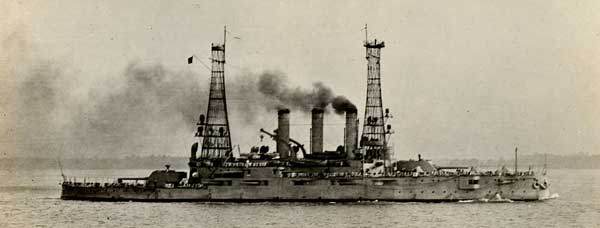

Union Iron Works with some of the naval ships it produced, early 1900s.

Source: San Francisco Maritime Museum Library

Potrero Point, where Pier 70 sits on San Francisco's eastern waterfront, was the most important center of western U.S. heavy industry for well over 100 years.

Before Potrero Point saw its first industrial development, it was part of the pasturage for Mission Dolores, later part of the large DeHaro ranch. After the conquest of California by the United States in the U.S. - Mexico War, a protracted legal struggle ensued and the DeHaro family eventually lost their claim to the land.

The area attracted early industrial operations because of its cheap land, deep-water access, and isolation from the more populated sections of the fast-growing city. This small cape of land, much enlarged and flattened over the decades, was the home of at least a half dozen major manufacturing and utility companies that played significant roles in the western and national economies, and in military and labor history. (Read more about Potrero Point geography.)

Early Boat and Wooden Shipbuilding

Ships were built in the area around Potrero Point and nearby Mission Bay as far back as the Gold Rush.

Boatyard at Potrero Point (probably belonging to Henry Owens), ca 1870.

Photo: Eadweard Muybridge/Bancroft Library

John G. North

The most famous early shipyard at Potrero Point was North's Ship Yard, owned by a Norwegian immigrant named John G. North (born Johan Gunder Nordtvedt). North came to California from Norway in 1850, worked the gold fields briefly but soon began building boats and ships (including river steamboats, bay and ocean schooners). His boat building operations lasted from 1852 to 1872 (from 1862 or so at Potrero Point). North had a great reputation for the quality of his boats and his integrity. Unfortunately, no pictures of North's Ship Yard have been found.

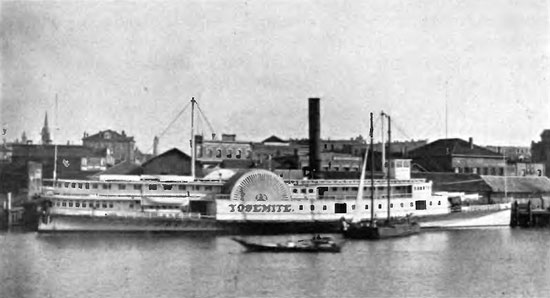

The Yosemite, one of several ferries built by John North at Potrero Point.

Read a 19th century magazine article about John North

Small boatbuilding and repair operations continued near Pier 70 even after the arrival of large-scale steel ship building in the 1880s. One significant boatbuilding operation was that of George Kneass & Sons, whose shed is still standing just north of Pier 70.

Early Industry at the Potrero (1850s - 1870s)

From the 1850s Potrero Point was also the site of two or three blasting powder manufacturers. As the area became more crowded the powder companies had to leave.

Tubbs Cordage Workers

Also dating from the 1850s was the thousand foot long ropewalk of the Tubbs Cordage Company at the southern edge of Potrero Point. It was founded by two brothers in the ship chandlery business who realized the west needed rope for its growing maritime and other industries. They recruited a group of skilled workers from New England who formed the core of the Tubbs workforce for decades. Tubbs imported raw materials from the Phillipines and became a world-wide concern.

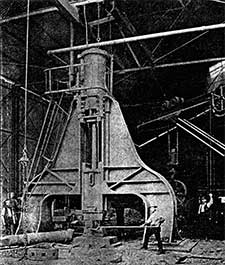

Banner from Pacific Rolling Mills Stock Certificate

Pacific Rolling Mills Forge

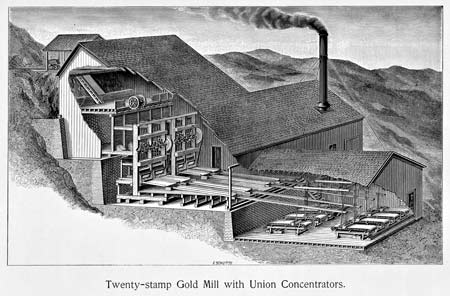

Other heavy industrial companies were located here as well. Pacific Rolling Mill operated at Potrero Point from 1866 until around 1900. (Its successor company then moved to 16th and Mississippi Streets nearby.) The first significant iron and steel mill in the west, Pacific Rolling Mill also produced machinery and specialized steel parts for the mining industry, construction, ship building, and rail equipment, including San Francisco's famous cable cars.

The Risdon Iron & Locomotive Company operated on the same property from 1900 until 1911. Risdon produced much mining equipment and developed some of the first and most successful gold dredgers.

Later the Spreckels Sugar refinery was built nearby, as was a gasworks that later evolved into PG&E. In addition, a barrel manufacturer, and several other companies were active at Potrero Point.

Union Iron Works

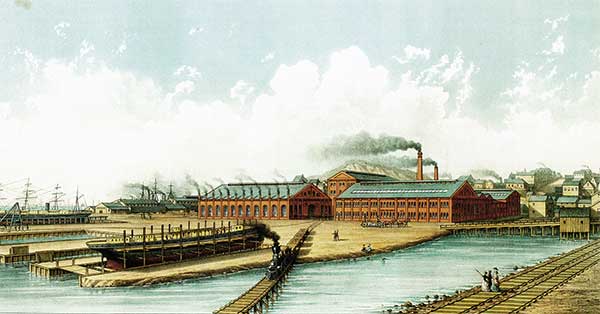

Union Iron Works Plant at Potrero, 1880s. Image: San Francisco Maritime Museum Library

In 1849 Irish immigrant Peter Donahue and two brothers established the first iron casting foundry in California, Union Iron and Brass Co. Soon known as Union Iron Works, it made many things, including architectural iron work used in many local buildings and powerful mining machinery that did much environmental damage in the gold country. Union Iron also produced marine engines at their shops near what is now First and Mission Streets. (In the early days, before Union Iron moved to Potrero, maritime operations were performed at Steamboat Cove near the present SBC Park.)

Peter Donahue sold the Union Iron Works in 1864. With the profits he founded San Francisco's first gas works, later to become PG&E, and developed local railroad lines.

Irving Scott Bets on Shipbuilding

Irving M. Scott

The Union Iron Works was then managed by Irving M. Scott, a talented and ambitious business man and engineer whom Peter Donahue had recruited years earlier. Irving Scott put his brother, Henry Tiffany Scott, in charge of the business side of the operation. Irving Scott designed innovative equipment used to mine the silver of the Comstock Lode in Nevada. It's estimated that Union Iron Works built most of the machinery used in the Comstock.

But Scott knew that the mining boom would not last forever, and that environmental curbs being put on the mining industry would also curb its need for his products. He also saw that the development of the west and the Pacific trade, along with the expansion of the railroads would soon lead to the need for large-scale local shipbuilding. He decided to gamble on building the first great west coast shipyard.

Scott travelled around the world to learn the most advanced shipbuilding technology. Back in San Francisco, he moved Union Iron in 1883 to the shoreline of San Francisco around Potrero Point on bay land that had been recently created by filling in the bay. (The land was acquired from the Pacific Rolling Mill Company in exchange for mining equipment.)

Union Iron Works in Scientific American Magazine

Scott used what he had learned during his travels to create state-of-the-art machine shops, foundries, and launching facilities. The layout of the shipyard was carefully designed to make the flow of work from workshops to shipways as efficient as possible.

Because it was isolated from the eastern manufacturing centers, Union Iron needed to be highly self-sufficient: it could produce virtually anything needed to build large steel ships in its own shops. It used steel and iron from the nearby Pacific Rolling Mills, but had to import armor plate from eastern mills.

Scott hired James Dickie, one of a family of local boatbuilders, to supervise shipbuilding operations.

Launching of the Arago, 1885. Source: San Francisco Maritime Museum Library

The plant built its first ship, a coal carrier called the Arago, in 1885. It was the first steel hulled ship built anywhere on the Pacific Rim.

Apprentices, 1906. Photo: Potrero Hill Archive Project

It was hard to find craftsmen with the skills to produce steel ships in a place where it had never been done before. Scott said he never recruited machinists and other skilled workers from abroad, but many qualified shipyard workers found their way to his shipyard, from Scotland, Ireland, England, Germany, and elsewhere. And Scott created an apprenticeship program that employed young boys for four years at low wages in return for the promise of learning a skilled trade. The rules stated the boys must be 16, but many were probably younger.

Many of the workers of the Union Iron Works and nearby plants lived in the immediate vicinity. The rough and tumble neighborhood of Irish Hill surrounded the plants and housed many immigrant Irish workers and some families who let rooms. A nearby section of Potrero Hill would later be referred to as "Scotch Hill" because many of these Scottish shipbuilders settled there. Dogpatch was home of many of the foremen and skilled workers.

Working conditions were tough for industrial workers in the 19th and early 20th century, at the Union Iron Works shipyard as at other plants. Sixty hour weeks were the norm. Unionization was resisted fiercely by management. Pay was a little better at Union Iron Works than at most east coast yards because of the shortage of qualified workers. Management encouraged loyalty through sponsorship of athletic and social activities.

Cruiser U.S.S. Olympia - Admiral Dewey's Flagship

Scott was a talented politician and businessman as well as technologist. He used political clout and pursuasion to convince Washington politicians that his new west coast yard could handle the challenge of building big, modern warships—something that had only been done in the east. He got his first government contract to build the U.S.S. Charleston, and went on to win dozens of other naval shipbuilding contracts. Many of the ships of the Spanish-American War, including Admiral Dewey's flagship, the U.S.S. Olympia, were built here. Scott, politically active and a prominent speaker, promoted American expansionism (which, incidently, would require more war ships from his plant.) The Olympia still exists, the oldest steel ship in the world, as a museum ship in Philadelphia.

Ferry Berkeley, built 1898

Another still-floating survivor of Union Iron Works production is the ferry Berkeley, one of 15 ferries built here, now a mainstay of the San Diego Maritime Museum.

Launching a warship, 1890s - Launchings were always major public events

Though the company built many civilian ships, the heyday of the Union Iron Works coincided with the expansion of the United States Navy from a modest, coastal defense force to a major multi-ocean naval force. Many great warships were built at the Potrero Yard, including the famed battleships Oregon, California, and Ohio.

President McKinley, a friend of Irving Scott, visited the yard in 1901 to participate in the ceremonial launch of the U.S.S. Ohio.

President McKinley comes to launch the USS Ohio in 1900.

Battleship U.S.S. Ohio - completed 1904

Ships were built for other countries as well; especially famous was the cruiser Chitose built for the Japanese navy.

Filmclip: See the launching of the Japanese cruiser Chitose.

Even though the Union Iron Works was successfully proving its ability to build world-class warships and civilian vessels, a significant amount of its business continued to be from mining and other non-maritime industry.

Gold Mill with Union Iron Works machinery - 1880s

Schwab of Bethlehem Steel Buys the Union Iron Works

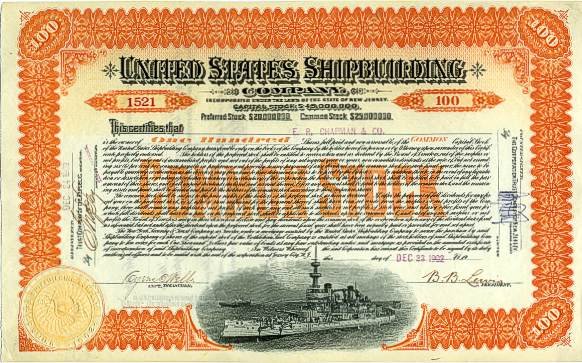

At the turn of the 20th century, Union Iron Works was sold to the United States Shipbuilding Corporation, a shadowy combine that had bought several U.S. shipyards. It soon went into receivership in what one observer called “one of the most amazing and disgraceful chapters in American Business History.” The assets of the combine, including Union Iron Works, were put up for sale.

The Union Iron Works was sold to Charles M. Schwab of the Bethlehem Steel Corporation in 1905 for $1 million. The sale took place in a public auction held on 20th Street. Schwab was widely believed to have engineered the demise of the U.S. Shipbuilding Corp. Whether or not that was true, he certainly benefitted from its collapse.

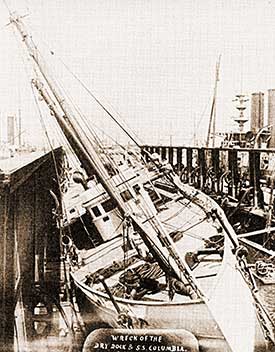

Shipyard Damage from 1906 Earthquake.

Source: San Francisco Maritime Museum Library

Shortly after the purchase of the shipyard, the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake struck, doing considerable damage to the plant. The biggest loss was the destruction of a specially constructed hydraulic drydock that had been the pride of the shipyard: a large ship, the S.S. Columbia, was in the drydock when the earthquake struck and was knocked off its supports— the drydock was irreparably damaged.

Charles Schwab

Charles Schwab was a brilliant steel man who had gone from being a mill hand to president of a major steel company in a few short years. He loved gambling, receiving great notoriety for his escapades in Monte Carlo. But he was also a serious and hard-driving businessman who intended to dominate west coast shipbuilding. In 1908, Bethlehem bought the Hunters Point drydocks, and eight years later purchased the 90 acre Alameda shipyard. In 1910, major improvements began on the Potrero yard that continued until World War I.

In 1911, Bethlehem's bought out its adjacent competition, the Risdon Iron Company, acquiring Risdon's drawings, patents, patterns, and hardware. Particularly valuable were Risdon's gold dredge designs and patents. (Risdon's land was sold to the United States Steel Corporation for a storage yard, though it was later acquired by the U.S. government and operated by Bethlehem as a shipyard.)

World War I

World War I was a great opportunity for Bethlehem: Its Bay Area shipyards were among the biggest producers of ships during the war. (Coincidentally, during the war Charles Schwab took a leave from Bethlehem and served as the head of the U.S. agency that managed naval production.)

Bethlehem Workers - World War I. Photo: UIW/Bethlehem

The Potrero yard launched an average of three destroyers a month, and Bethlehem built a total of 66 destroyers and 18 submarines during the first world war.

The shipyard specialized in destroyers and subs in World War I.

After WWI shipbuilding continued but at a much slower pace. By the late 1930s, though, with war looming, Bethlehem began to modernize and upgrade the Potrero Yard. A number of new buildings were constructed, and by the time World War II began Potrero was one of most productive shipyards in the country.

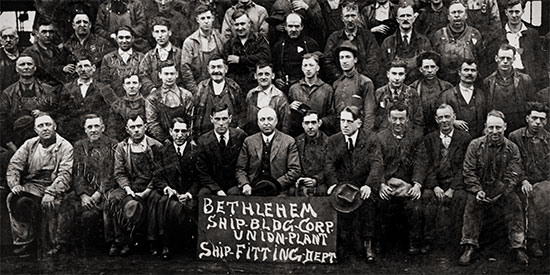

Shipfitters, 1923. Photo: Potrero Hill Archives Project

World War II

During the war, approximately 18,500 men and women were employed here, working three shifts a day, seven days a week. Finding skilled workers during war time was a huge challenge, and much was done to train new workers, and to organize shipbuilding so that less skilled people could do what the highly skilled people had done before.

Destroyer Escort U.S.S. Fieberling - built in 24 days!

At the height of the war effort productivity was tremendous: the destroyer escort Fieberling was built in 24 days, start to finish. Though Liberty ships and other simpler ships could be built faster, to build a modern warship in that amount of time was an incredible achievement.

During the war, Bethlehem's Potrero yard produced 72 vessels (52 for combat) and repaired over 2500 navy and commercial craft.

World War II was the most productive time in the shipyard's history.

Bethlehem Shipyards at Pier 70 (along with Alameda and Hunters Point, both also managed by Bethlehem) was one of several major yards that made the San Francisco Bay Area the most productive shipbuilding area in the U.S. during World War II, and probably the most productive in world history. Other sites included Marinship in Marin, the Kaiser Shipyards in Richmond, and Mare Island in Vallejo. Many smaller yards were active as well, producing smaller craft.

Labor Organizing at the Shipyard

Machinists' Strike, 1941. Photo: San Francisco Public Libary

The labor history of the shipyards at Potrero is not well-documented. Bethlehem Shipbuilding, like the Union Iron Works, fought hard to keep unionization out of the shipyards. Strikes, some of them protracted, occurred periodically throughout the active shipbuilding period, including during the war years and immediately after. One important strike in the spring of 1941 halted major naval shipbuilding for a month and a half, leading to the intervention of President Roosevelt in efforts to end the strike. Members of the machinist union's local resisted the federal government and their own national leaders and persisted in the strike. They succeeded for the first time in achieving a closed shop at Bethlehem.

Filmclip: See 1917 Strike Footage

The Post-War Years

U.S.S. Bradley - Last Ship Built at Pier 70

Shipbuilding went into immediate decline after the war, but picked up somewhat in the mid-1950s. In all, seventeen ships were built after the war, including several tankers, freighters, and four frigates for the U.S. Navy. The last ship built was the frigate U.S.S. Bradley, delivered on May 11, 1965.

Though shipbuilding had come to an end, the Potrero yard continued to build large barges well into the seventies. Another significant project was making the large steel tubes that would take BART trains under the Bay. In 1967, 57 sections, each 325 feet long and weighing 800 tons, were fabricated here.

BART Tube

Ship repair continued, but by the 1970s the Potrero yard was suffering from the depressed shipping industry in the U.S. In 1979, the Bethlehem Corporation celebrated its 75th anniversary and the Potrero yard was recognized as the oldest active civilian shipyard in the US, but active shipbuilding would no longer take place here.

On November 1, 1982, the City of San Francisco became owner of the Potrero yard property, paying Bethlehem one dollar. Todd Shipyards purchased the machinery and other assets of Bethlehem's San Francisco operation for $14 million. Todd repaired ships here for some years.

Cruise Ship in Drydock for Repair. Photo: Ralph Wilson

For many years BAE Systems San Francisco Ship Repair continued the ship repair business on about 15 acres of land in the northeast of Pier 70 leased from the Port of San Francisco. At the end of 2016, BAE ended their operation of the shipyard and another company briefly operated it. However, a business dispute ended that arrangement. Currently, the Port of San Francisco is working to find a tenant to resume shipyard operations here. One of the largest repair facilities on the west coast, the facilities at Pier 70 can handle ships of almost any size, including very large cruise ships. In recent years, several hundred union shipyard workers were employed here on an average working day, and Pier 70 was the largest heavy industrial operation in San Francisco.

Much of the historical architecture built to support shipyard operations over the years is still standing, though in serious need of repair. One of these buildings, the machine shop, dating from 1883, was used continuously until early 2004, when seismic concerns forced the Port to close the building. Rehabilitation of the most important historic buildings is well underway.

Machine Shop Building 113. Photo: Ralph Wilson

The Port of San Francisco actively seeks new uses for these historic buildings, uses that meet the needs of the present and future, and respect the heritage of the past.

by Ralph Wilson

Please consider this an informal, non-scholarly history. Any mistakes are my own.

Sources:

A great source about Pier 70 history with emphasis on historic architecture as well as labor history is the National Registry Nomination documentation for the Union Iron Works Historic District.

The San Francisco Maritime Museum Library in Fort Mason is the repository for the Union Iron Works and Bethlehem Shipbuilding San Francisco Yard archives.

A fascinating chapter on the Union Iron Works and Irving Scott can be found in "Imperial San Francisco: Urban Power, Earthly Ruin" by Gray Brechin (UC Press).